Chapter 6

History

In her estate, Mary Clark Thompson evoked cultures far away in time and space. Among the many “antique” sculptures decorating house and garden there are a few really ancient ones. They all originate in Europe, more precisely Italy. Our catalogue tells the life story of each of them. Although we are lacking many of their “biographical” data, we can say one thing for sure: before arriving at Sonnenberg they had changed shape, owner and home multiple times.

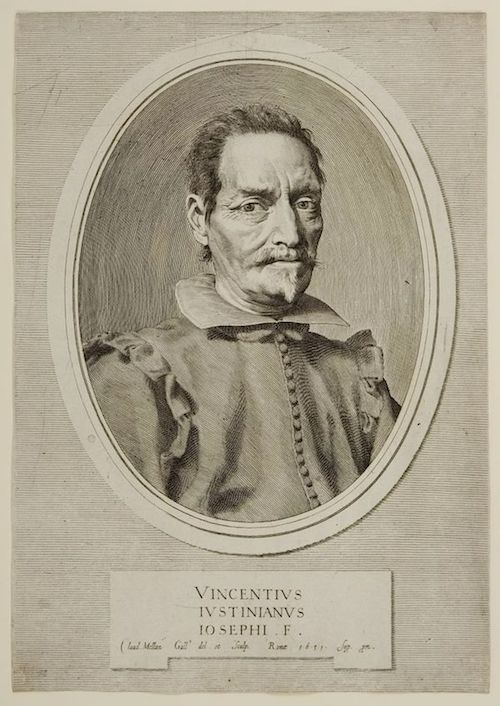

Vincenzo Giustiniani and his collection

At some point in their history they all belonged to a collection of ancient Greek and mostly Roman sculptures assembled by Marquis Vincenzo Giustiniani the Younger (1564-1637), a banker, art collector and nephew of a famous cardinal.

Born on the Greek island of Chios, he hailed from a family of bankers based in the northern Italian city of Genoa. But he grew up in Rome, where thanks to the family’s wealth and connections to the church he owned several palaces and could pursue his passion: reading, studying and—collecting art.

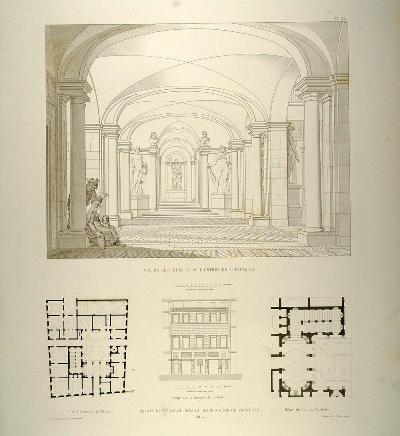

Palazzo Giustiniani, Rome. Built in the late 16th century; today the residence of the president of the Senate of the Republic of Italy.

Photo source.

Vincenzo had a predilection for painters such as Titian, Raphael or Caravaggio. But, like so many of his peers, he also collected ancient marbles. Since the Renaissance, massive amounts of such sculptures had been found in the city, during construction works or in excavations led by members of the church—mostly cardinals who tried to secure the treasure for their own collections. There is no evidence that Marquis Giustiniani undertook such excavations. Instead, it seems, he bought the sculptures from art dealers which leaves us with many mysteries. We do not know where exactly the pieces in Vincenzo’s collection were found. Most probably they came from Rome and its surroundings. In many cases, we can only guess when they were made. Taste at the time required whole, unbroken figures. Art dealers, sculptors and conservators (often one and the same person) therefore completed the ancient fragments to their best knowledge and/or interest, sometimes with fragments from other ancient sculptures, sometimes with new pieces. The Giustiniani marbles at Sonnenberg are either assembled from various ancient fragments, entirely new sculptures (of the 17th or 18th centuries), or a hodge-podge of old and new.

Vincenzo might not have been aware of what exactly was ancient and what was new. And it probably did not matter. His collection was one of the largest ever assembled by a private collector. Unlike his paintings, his antiquities had the reputation of lacking real masterpieces (in the early 19th century German playwright August von Kotzebue even called what remained of it “the junk box of antiquity”1). The marquis found a way to enhance their value. He commissioned famous artists of the time to draw and then etch many of the statues and reliefs to compile a catalogue—the first ever of a collection of antiquities—in two sumptuous volumes. It is not an exhaustive documentation. Which sculptures made it into this “paper museum” of Galleria Giustiniana (1636/1637 - 1640), is therefore all the more telling for the taste and time of their owner. Two pieces that Mary Clark Thompson had once displayed in the breakfast bower at Sonnenberg are depicted in the catalogue: the Apollo and the now missing female statue.2

Breaking up the collection

Vincenzo’s heirs (he himself died childless) did eventually add other items to the collection, but over time, because of ignorance and financial needs, they sold it off bit by bit. Other aristocrats in Rome and in the rest of Europe jumped at the occasion. Today, numerous paintings and sculptures are housed in the Vatican and the Capitoline Museums, or remain in private possession (such as in the Albani or Torlonia collections in Rome). Still more can be found in Paris, Berlin or London. With the death of the last Giustiniani in 1826, the palace in Rome changed hands multiple times, until, in 1901, the Masonic Lodge “Grand Orient of Italy” (Grande Oriente d’Italia) made it their headquarters, its Grand Master being the Mayor of Rome himself.

Photo of the inner courtyard of the Palazzo Giustiniani, at the time it housed the Masonic Lodge.

Photo source.

The turn of the century coincides with the sculpture collection’s final divestiture. After the reunification of Italy in 1861/1870, many impoverished aristocratic families tried to make profit of their remaining possessions, and so did institutions or other administrative entities. While the young nation state neither had the financial means nor (yet) an appropriate legal apparatus at hand to prevent sell out of its antiquities, more or less trustworthy art dealers and agents were on the spot. A long-standing tradition, especially in Rome, where ancient works of art of great fame had been discovered since the Renaissance, trading antiquities to the rest of Europe and beyond flourished. By the late 19th century, many foreigners had settled in the eternal city, who would eventually work more or less officially as agents for their patrons abroad. Main protagonists on the ground for the sale of (part of) the remaining Giustiniani collection to the United States would be eminent Italian art dealer Giuseppe Sangiorgi (1850-1928) and American Reverend Robert Jenkins Nevin (1839-1906), for 37 years rector of S. Paul Within the Walls Episcopal Church in Rome.

Negotiations with the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York

Having opened its doors to the public in 1870, the Metropolitan Museum of Art was a toddler compared to most of its European counterparts, when it started to acquire antiquities.3 But its foundation coincided with the rise of the United States’ economic power. The museum therefore immediately became a serious competitor on the art market.

Ancient Greco-Roman art however, especially sculpture, was not so easy to find at the time. The Museum had no connections to an excavation that would have provided access to such material, and some of the relevant host countries, like Greece, would not allow exportation of antiquities anyway. If one were not to rely on looting (an option that still too many museums opt for up to this day), the best opportunity was to get ahold of sculptures in old European collections.

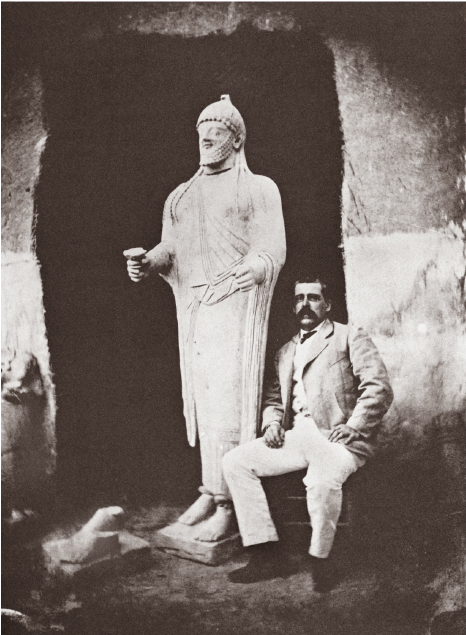

A major (if contested) acquisition of the young Metropolitan Museum had been the collection of Cypriot Art, secured in 1874-76 by its first director, Italian-American Consul and archaeologist General Luigi Palma di Cesnola (1832-1904). But Cypriot culture was considered marginal and strange. If the museum wanted to compete (also with its main rival on American shores, the Boston Museum of Fine Arts) it had to own “classical”, i.e. Greco-Roman sculpture.

Luigi Palma di Cesnola in the director’s office of the Museum; photo, City Museum of New York.

Photo source.

The Giustiniani collection coming up for sale therefore offered a unique opportunity. Negotiations started in 1902, with Cesnola, secretary of the Museum and its then director Frederick Rhinelander (1828-1904) on the American side, art dealer Sangiorgi and Reverend Nevin, at some point declared official agent of the museum, in Italy. The many letters, cables and reports that traversed the Atlantic or circulated among the trustees, at times several per week (today all kept in the Archives of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York), betray a frantic activity.

Sangiorgi is eager to sell the group of sculptures, their number varying between 57 and 64, as a whole. As much businessman as Italian national proud of his country’s cultural heritage, he bridles at splitting up the “historical” collection. Cesnola, Italian himself, but with allegiance to the United States, sees a unique opportunity to boost the young museum’s holdings in one fell swoop—for a relatively moderate price at that—and convinces Rhinelander, who eventually would purchase two Giustiniani marbles for himself. Yet, resistance among the trustees is tenacious. In line with the collection’s old reputation, J. P. Morgan reportedly considered the pieces on offer “rubbish”.4

While conceding that they are not of highest quality from an artistic point of view, Cesnola emphasizes the marbles’ archaeological value. He even refers to the (unsubstantiated) claim they once decorated the baths of Roman emperor Nero, having been discovered underneath the Palazzo Giustiniani. Still, a contemporary sculptor is solicited for an evaluation of the sculptures’ artistic value. Finally, an agreement is made: the Giustiniani marbles will be bought if public funds can be made available. This is where Mary Clark Thompson (or Mrs Frederick Ferris Thompson) comes in. A friend of Rhinelander’s, she agrees, on November 22, 1902, to contribute up to $60,000 for securing the sculptures for the Metropolitan Museum.5

After two years of intense negotiations the “Giustiniani marbles” are finally removed from the Palazzo Giustiniani and shipped overseas. Art dealer Sangiorgi might have rubbed his hands, but not everybody liked to see the sculptures go, such as archaeologist Giulio Emanuele Rizzo. Asked to compile a last inventory, he laments the sellout of his country’s cultural heritage by the “brutal force of gold” (i.e. money) with which museums overseas augment their holdings.6 And he doubts that the objects, once bereft of their historical context, will ever be properly understood and appreciated.

Rizzo’s fears were not entirely unjustified, at least initially. The discussions preceding the collection’s purchase, mentioned above, give insight into a formative period for American art museums. Should these museums, in a more democratic fashion, instruct people about history, art and taste? Or cater to connoisseurs and affluent art lovers? Should they, in consequence, display historically significant, but otherwise not necessarily outstanding objects? Or only unique, first rate works of art? In sum, should they educate the people, or celebrate the nation’s growing economic and cultural power?

At the time, the Giustiniani marbles sat uncomfortably between these two options. They (or most of them) were ancient originals, not plaster replicas, cheap copies or fakes. None of the marbles, however, that came to America were considered famous or of artistically high value. As Rome based American sculptor Moses Jacob Ezekiel (1844-1917) writes in his report for the museum, the sculptures might serve for study or as decorative pieces.7 Also, having been heavily restored in the 17th centuries and later, it was not immediately clear which parts of the statues to regard as ancient or valuable.

When they were removed from the Palazzo in Rome, where most of them had been in the open air, decorating niches or walls, the sculptures were in bitter need of cleaning and repair. Restricted to a minimum before shipping, proper restoration was arranged for at the museum. Yet, as one can gather from letters in the archives, the Metropolitan’s curators soon despaired of the pieces with their complicated history. It is only in 1906 that some of the marbles finally went on display. In a newspaper article then assistant director Edward Robinson (1850-1931) explained the delay with the difficulties encountered while doing restoration work. Other documents suggest that this is not the full story…8

Soon after their arrival, the Giustiniani marbles lost their two most ardent advocates at the museum. In 1904, both Cesnola and Rhinelander passed away. Restoration of the sculptures for display might afterwards have become less urgent. In April 1905, Mary Clark Thompson inquires about the status of the pieces and asks whether, since they are not on show, she might get them back. Her plan is to give them to institutions of higher education such as Vassar and Williams College, where her late husband Frederick Thompson went to school, and eventually keep a portion for her mansion at Canandaigua.

Mansion at Sonnenberg Gardens.

Photo: Annetta Alexandridis.

Mansion at Sonnenberg Gardens.

Photo: Annetta Alexandridis.

Sonnenberg Gardens

Finally, both parties agree to split up the collection into three parts. The first tier will stay at the Metropolitan museum, the second would go to the designated colleges, and the third to Sonnenberg Gardens. How little appreciated—if not unwanted—the collection was transpires in some of the archival documents. When Mary Clark Thompson asks for help with restoring and mounting the sculptures at her place, the museum recommends Luca Vescia, a New York based sculptor recently dismissed from the museum’s conservation services. Even more blunt is Edward Robinson, the museum’s assistant director. Upon receipt of a shipment of sculptures, Richard A. Rice, President of Williams, had inquired about the significance of the marbles.9 In a letter, stamped “confidential”, Robinson replies:

“While President of this Museum the late Mr. Rhinelander urged the purchase of this collection upon the Trustees. As they declined to buy it, he persuaded his friend, Mrs. Thompson, to present it to the Museum … [The sculptures were] inspected by the Committee on Sculpture, the members of which were of the opinion that some of the figures had a sufficient value as objects of decoration to warrant their acceptance, but that others had not even this much in their favor … After my arrival here Mrs Thompson … said that if there were any pieces among those rejected which were good enough to present to Williams and Vassar College, even though they might not be considered up to the standard of the Metropolitan Museum, she would like to give them to those institutions … taking the balance to her own country estate at Canandaigua. You will thus see that the collection was divided into three classes based on merit, and when I say that those accepted by the Museum are not regarded as by any means first-rate examples you will perhaps draw your own inferences as to the remainder …”.

No wonder that the sculptures at Williams stayed unpacked until 1923; and that both Vassar and Williams never seem to really have embraced Mary Clark Thompson’s gift. Both institutions later sold some or all of their sculptures. The whereabouts of these divested marbles are unknown, except for two formerly at Williams: a statue of Mercury, currently at the Villa Terrace Decorative Arts Museums in Milwaukee, WI; and a statue of the Roman emperor Septimius Severus (146-211, ruled 193-211) at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts in Richmond, VA.10

The Metropolitan Museum later changed its attitude. Today, the Giustiniani marbles—if for the most part stripped to their later restorations—play a prominent role in its ancient art galleries.

The only site where the rejected sculptures seemed to have found a cherished place soon after their arrival on the other side of the Atlantic was Sonnenberg Gardens. To judge from old photographs, most of them were put on display in the breakfast bower among plants, a fountain, and furniture.

True, Mary Clark Thompson seems to have appreciated the marbles less for their ancient content than their decorative value as garden sculpture. But even so, she rescued “her” Giustiniani marbles from “lifelong” confinement to crates and from invisibility.

Unfortunately, two among the figures assigned to Sonnenberg are missing: a group of two wrestling men and the under life size statue of a woman in long garment. Let’s hope Mary Clark Thompson did not rescue them in vain!

A.A.

Ithaca, NY

December 2017

1 A. v. Kotzebue, Ausgewählte prosaische Schriften, Vienna 1842-43, 126 (“eine Rumpelkammer von Antiken”).

2 Galleria Giustiniana II, plate 113 and I, plate 126.

3 The very first object to enter the museum collection actually was a Roman sarcophagus; see their blog entry.

4 Letter from L. di Cesnola to treasurer Fahnestock; Oct. 10, 1902 (Metropolitan Museum of Art, Archives).

5 Letter by Mary Clark Thompson to F. W. Rhinelander on Nov. 22, 1902 (Metropolitan Museum of Art, Archives).

6 G.E. Rizzo, Sculture antiche del Palazzo Giustiniani (Rome 1905) 12 (“con la forza brutale dell’oro”).

7 Letter to Trustee Harris C. Fahnestock from Oct. 9, 1902 (Metropolitan Museum of Art, Archives): “There are no masterpieces among them, but on the whole it forms a creditable, historically artistic, and archaeologically interesting collection of genuine Antique Sculpture … Nothing gives such an air of refinement and artistic feeling to any Art Building and the Grounds around it, as pieces of authentic antique statuary – however mutilated they may be – and hence such pieces as are not considered as up to the mark for the museum itself, could well be used to decorate the stairways, niches, walls and gardens around the Museum.”

8 New York Times, May 7, 1906 on New Marbles and Vases Acquired by Museum.

9 Letter to President Rice from October 2, 1906 (Metropolitan Museum of Art, Archives).

10 Septimius Severus statue at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts.