Chapter 7

The Sculptures, Revisited

Section 5

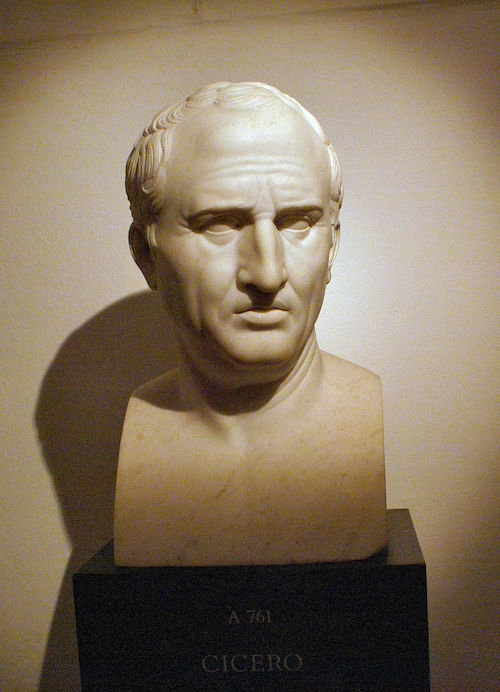

Bust of Cicero

The marble bust of a middle-aged man going bald on his forehead and with a big, slightly curved nose, represents the famous Roman politician, philosopher and writer Marcus Tullius Cicero (106-43 BCE). Honored by the Roman Senate for having uncovered a conspiracy against the Roman Republic in 63 BCE (see his Orations against Catiline), he later fell victim to the unrest during civil war. After the murder of Julius Caesar in 44 BCE he was proscribed and killed while trying to escape.

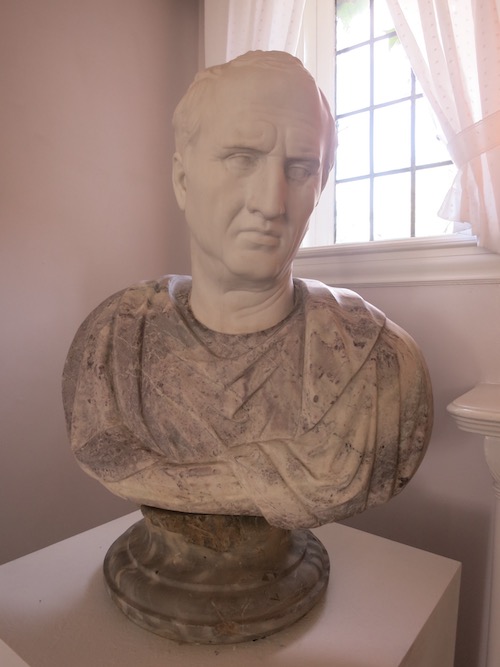

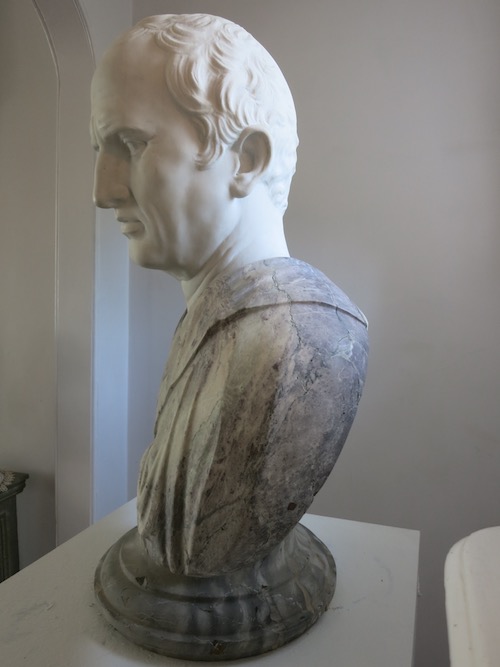

Sonnenberg bust of Cicero.

Photo: Annetta Alexandridis.

A prolific writer, his works continued to have an effect far beyond antiquity. His orations, his many letters, his political-philosophical writings such as On the State, On the Laws, On Duty, On the Nature of the Gods and On Friendship to name but a few, were studied by intellectuals since the Middle Ages and became part of higher education. The Founding Fathers saw Cicero as a model statesman; his works constituted core reading in Liberal Arts curriculum in the United States in the 19th and 20th centuries. To this day, many towns in this country bear his name (such as Tully in Onondaga County, NY).

Proof of Cicero’s renown among the ancients are the many portraits of him that have survived. The bust at Sonnenberg, however, is modern, as the pristine state of the head suggests. Yet it copies an ancient model, probably the bust in the Capitoline Museums in Rome from the 1st century BCE.

The Sonnenberg bust combines pieces carved from different colored marble. The white head is mounted on a light purple bust which in turn sits on a grey pedestal. A closer look at the proportions reveals that the pieces were not made for each other: the bust is too small for the head; the pedestal too big for the bust. But even if the proportions were correct, the single elements would not match. For example, at Cicero’s lifetime, portrait busts were generally smaller and did not include the shoulders. Also the toga, the characteristic garment of the Roman man, was at the time tighter and draped in a different fashion than featured on the bust.

Sonnenberg bust of Cicero.

Photo: Annetta Alexandridis.

Although this kind of “hodge-podge” is characteristic for the 17th century, the bust was probably not part of the Giustiniani collection until later. The numerous inventories of the Palazzo Giustiniani put together since 1638 do not mention it until 1881.1 Admittedly, most of the entries offer rather generic descriptions. And the bust might have figured under another name, as portraits of Cicero were not identified until the 19th century. But the head itself seems to have been carved in the 18th or early 19th century.2 A very pure white marble and the interest in relative precise copies of ancient works are characteristic of this time. A portrait of Cicero by the famous Danish neoclassicist sculptor Bertel Thorvaldsen (1770-1844), for example, relies on the same model as the Sonnenberg piece.

Where was the portrait displayed in its new home across the Atlantic? None of the old photos depicting the gardens or interiors of the mansion show the bust. It was clearly not considered decorative sculpture for the intimate garden or the breakfast bower. Did Mary Thompson know it represented Cicero? The list compiled by the Metropolitan Museum to document partitioning of the Giustiniani sculptures labels it “philosopher.”3 Either way, Sonnenberg’s landlady might have found it fit to grace the mansion’s library. Today, the bust is on show on the second floor.

A.A.

Ithaca, NY

December 2017

1 Friedrich Matz – Friedrich von Duhn, Antike Bildwerke in Rome, mit Ausschluss der grösseren Sammlungen, Leipzig 1881, 494 no. 1812: “On a modern bust; head of Cicero. Modern?”

2 Reverend Nevin, who inspected the collection for the Metropolitan Museum also writes in a letter to President Rhinelander on July 29, 1902 “… the “Cicero” is a little more over one hundred years old….” (Metropolitan Museum of Art, Archives).

3 Metropolitan Museum of Art, Archives.